“Often a bridesmaid, never a bride” – Listerine used this slogan to draw attention to its mouthwash in the 1920s. Anyone who buys the product avoids the risk of not recognizing their own bad breath. The recipe for success of the “dark art of marketing” boiled down to the fear – as a possible consequence – of ending up as a desperate bridesmaid.

Source: Oscar Keys on Unsplash

Companies are no longer reliant on this kind of courting of anxiously obedient employees, users or consumers. If you want to be remembered, you need to tell stories that empower the target group rather than scare them. With the heroine’s journey model, companies are building on the principle that made the Listerine advertising slogan one of the most successful in the 20th century, but without relying on women’s fears and supposed shortcomings.

Campbell vs. Murdock: The empowerment of the heroine

Storytellers are reflecting on the hero’s journey, as discovered by myth researcher Joseph Campbell in the 1940s. Campbell explicitly did not understand the “hero” in the “Hero’s Journey” as a generic masculine. His argument was: “Women don’t need to make the journey, they are the place everyone is trying to get to”. With this explanation, he also dismissed a “heroine’s journey” out of hand.

Den Ansatz einer Heroines Journey hatte Maureen Murdock, eine Psychotherapeutin und Schülerin von Joseph Campbell, in “Woman’s Quest for Wholeness” als Antwort auf Campbells Modell der Heldenreise entwickelt. Ihr missfiel, wie passiv weibliche Figuren in den typischen Mythen und Epen repräsentiert waren. Als „Beiwerk“ für die maskulinen Protagonisten und für deren Entfaltung zwar wichtig, fehlte es ihnen an eigener Entwicklung. Grund genug, weiterzudenken, was eine gute Geschichte ausmachen kann. Murdock erklärte, dass die Reise der Heldin eine Heilung sei. Die Verwundung des Weiblichen sei tief in ihr und in der Kultur vorhanden. So beschriebt sie den Nährboden, auf dem letztlich auch der Erfolg von “Often a bridesmaid, never a bride” gründete.

Bildquelle: Mashup Communications nach der Heldenreise von Joseph Campbell und Christopher Vogler

Stages of the heroine’s journey

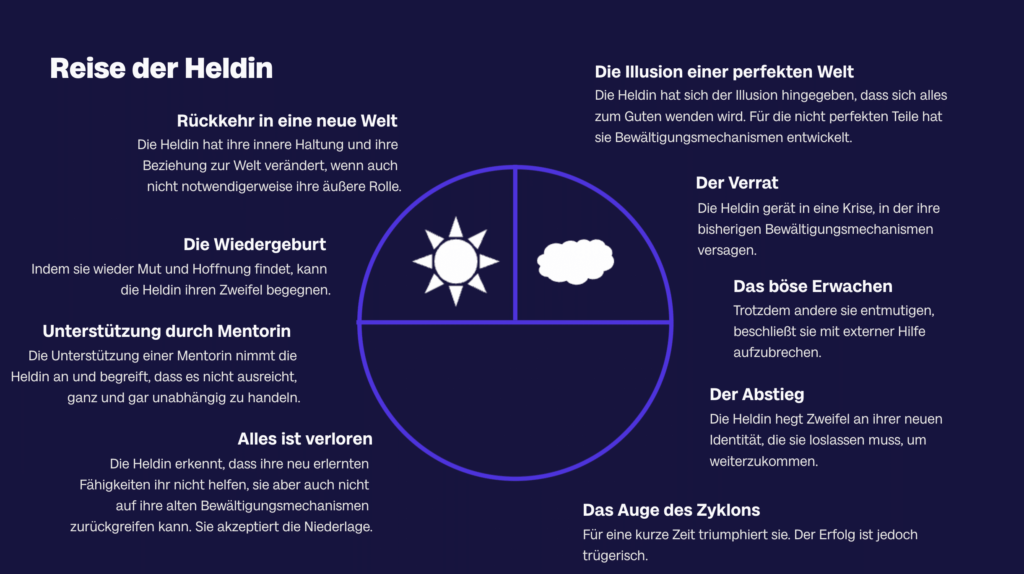

Victoria Lynn Schmidt made Murdock’s “heroine’s journey” approach fruitful for literature and described nine stages that can be exchanged and repeated as in the classic “hero’s journey”. The focus of the character’s motivation shifts away from the heroic epic, in which we have to slay the proverbial dragon in order to survive, towards survival within the family, community or society. The heroine takes the following steps on her journey:

Image source: Mashup Communications based on Heroine’s Journey by Victoria Lynn Schmidt

The illusion of a perfect world The heroine believes that the world she lives in is perfect. She has given in to the illusion that everything will turn out well. She has found coping mechanisms, such as naivety, denial or submission, to deal with parts of the world that may not be ideal. This is also the starting point of the Barbie movie story.

Betrayal or disillusionment The heroine finds herself in a crisis in which her previous coping mechanisms fail. The illusion of a perfect world is shattered. The crisis can be a personal betrayal, their previous world view proves to be wrong or their previous coping mechanisms become unhealthy.

The rude awakening At first, the heroine does not want to accept her current state. Others discourage her, but the heroine nevertheless decides to do something about her conflict. She looks for external help and guidance and can fall back on aids from her perfect world to help her on her way.

The descent: Passing through the gate The heroine has doubts about her new lifestyle or her new identity. However, in order to move forward, she has to give up her tools and let go of the doubts that are holding her back. The heroine may experience anxiety, shame or guilt about expressing herself and letting go of relationships that no longer work for her.

The Eye of the Cyclone For a short time, the heroine triumphs. However, the success is deceptive and does not last because, for example, people around them do not want to be led by women for long, or the men around them begin to undermine them. In another variant, she has to try to fulfill several roles, some of which are contradictory and impossible for a single person to fulfill.

All is lost The heroine realizes that her newly acquired skills are not helping her, but that she can no longer fall back on her old coping mechanisms either. The situation around her deteriorates and she has no choice but to accept defeat.

Support from a mentor The heroine finds support in a mentor who stands by her side. The heroine accepts the help of her supporters and realizes that it is not enough to act completely independently.

Rebirth or moment of truth Thanks to the support she has received, the heroine regains her courage and hope. She understands her place in the world and knows how to face her doubts. She sees the world and her role in it with different eyes.

Return to a new world The heroine sees the world as it really is. She understands herself better. Their inner attitude and their relationship to the world has changed, although not necessarily their outer role.

Gender types vs. gender

Gail Carrigers further developed the model of “The Heroine’s Journey”. For her too, the heroine’s journey, unlike the hero’s journey, is not about heroic self-sacrifice, but about the heroine finding and maintaining community and connection. Gail Carriger makes a clear distinction between gender stereotypes and gender: Harry Potter, for example, is a heroine’s journey and the first Wonder Woman film is a hero’s journey. The young Potter finds inner healing over the loss of his parents by maintaining a community of friends, while Wonder Woman achieves recognition in the outside world through self-sacrifice.

Conclusion: Companies as mentors

Whether heroine’s journey or hero’s journey, companies create successful stories when they themselves slip into the role of mentor and support their target group – the true heroes – with advice and assistance and sometimes helpful objects. How well marketing and PR professionals succeed in empathizing with their target group and empowering them to become heroes ultimately determines the success of a brand. The concept of the heroine’s journey is a valuable tool that can be put to good use in corporate communications.